JAPAN Celebrating Shichi-Go-San

November 15

Shichi-Go-San (七五三, seven-five-three) is a traditional rite of passage and festival day in Japan

for three and seven year-old girls and three and five year-old boys, held annually on November 15.

As Shichi-Go-San is not a national holiday, it is generally observed on the nearest weekend.

History

Shichi-Go-San is said to have originated in the Heian Period amongst court nobles who would celebrate the passage of their children into middle childhood. The ages three, five and seven are consistent with Japanese numerology, which dictates that odd numbers are lucky. The practice was set to the fifteenth of the month during the Kamakura Period. The festival is said to have started in the Heian period (794-1185) where the nobles celebrated the growth of their children on a lucky day in November.

Over time, this tradition passed to the samurai class who added a number of rituals. Children—who up until the age of three were required by custom to have shaven heads—were allowed to grow out their hair.

Boys of age five could wear hakama for the first time,

while girls of age seven replaced the simple cords they used to tie their kimono with the traditional obi.

The Meiji period, also known as the Meiji era (明治時代 (Meiji-jidai)), is a Japanese era which extended from 1868 until 1912.

By the Meiji Period, the practice was adopted amongst commoners as well, and included the modern ritual of visiting a shrine to drive out evil spirits and wish for a long healthy life.

Current practice

The tradition has changed little since the Meiji Period.

“the “Dog Deity” statue, also with a cub,

which is said to bring easy childbirth to the pregnant women who are rubbing it…”

While the ritual regarding hair has been discarded, boys who are aged three or five and girls who are aged three or seven are still dressed in kimono—many for the first time—for visits to shrines.

Three-year-old girls usually wear hifu (a type of padded vest) with their kimono. Western-style formal wear is also worn by some children. A more modern practice is photography, and this day is well known as a day to take pictures of children.

Chitose Ame

Chitose Ame (千歳飴), literally “thousand year candy”, is given to children on Shichi-Go-San. Chitose Ame is long, thin, red and white candy, which symbolizes healthy growth and longevity.

It is given in a bag with a crane and a turtle on it, which represent long life in Japan.

Chitose Ame is wrapped in a thin, clear, and edible rice paper film that resembles plastic.

Obi

Obi (帯, おび, , literally “sash”) is a sash for traditional Japanese dress, keikogi worn for Japanese martial arts, and a part of kimono outfits.

The obi for men’s kimono is rather narrow, 10 centimetres (3.9 in) wide at most, but a woman’s formal obi can be 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and more than 4 metres (13 ft) long. Nowadays, a woman’s wide and decorative obi does not keep the kimono closed: this is done by different undersashes and ribbons worn underneath the obi. The obi itself also requires the use of stiffeners and ribbons.

There are many types of obi, and most of them are for women: wide obis made of brocade and narrower, simpler obis for everyday wear. The fanciest and most colourful obis are for young unmarried women. The contemporary women’s obi is a very conspicuous accessory, sometimes even more so than the kimono robe itself. A fine formal obi might cost more than the rest of the entire outfit.

Obis are categorised by their design, formality, material, and use. Informal obis are narrower and shorter.

Women’s obi types:

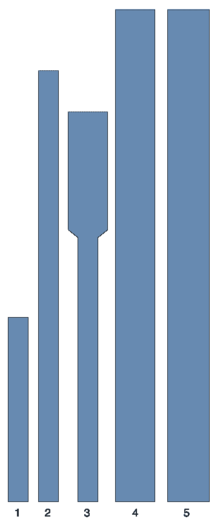

Women’s obis in scale:

1. tsuke/tsukuri/kantan obi

2. hanhaba obi

3. Nagoya obi

4. Fukuro obi

5. Maru obi

Tsuke obi is much shorter than the other types of obi.

The separate bow part of a tsuke obi is attached to the waist part with a metallic hook made by bending from wire.

Girl wearing a ‘yukata’.

The reversible obi had been folded to reveal the black underside, creating an effect.

- Darari obi (だらり帯) is a very long maru obi worn by maiko. A maiko’s darari obi has the kamon insignia of its owner’s okiya in the other end. A darari obi can be 600 centimetres (20 ft) long.

- Fukuro obi (袋帯, , “pouch obi”) is a grade less formal than a maru obi and the most formal obi actually used today. It has been made by either folding cloth in two or sewing two pieces of cloth together. If two cloths are used, the cloth used for to make the backside of the obi may be cheaper and the front cloth may be for example brocade. Not counting marriage outfits, the fukuro obi has replaced the heavy maru obi as the obi used for ceremonial wear and celebration. A fukuro obi is often made so that the part that will not be visible when worn are of smooth, thinner and lighter silk. A fukuro obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 360 centimetres (11.8 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long.

When worn, a fukuro obi is almost impossible to tell from a maru obi. Fukuro obis are made in roughly three subtypes. The most formal and expensive of these is patterned brocade on both sides. The second type is two-thirds patterned, the so-called “60 % fukuro obi”, and it is somewhat cheaper and lighter than the first type. The third type has patterns only in the parts that will be prominent when the obi is worn in the common taiko musubi.

- Fukuro Nagoya obi (袋名古屋帯) or hassun Nagoya obi (八寸名古屋帯, , “six inch Nagoya obi”) is an obi that has been sewn in two only where the taiko knot would begin. The part wound around the body is folded when put on. The fukuro Nagoya obi is intended for making the more formal, two-layer variation of the taiko musubi, the so-called nijuudaiko musubi. It is about 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) long.

- Hakata obi (博多帯, “obi of Hakata”) is an unlined woven obi that has a thick weft and thin weave.

- Hoso obi (細帯, “thin sash”) is a collective name for informal half-width obis. Hoso obis are 15 centimetres (5.9 in) or 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide and about 330 centimetres (10.8 ft) long.

-

- Hanhaba obi (半幅帯 or 半巾帯, , “half width obi”) is an unlined and informal obi that is used with a yukata or an everyday kimono. Hanhaba obis are very popular these days. For use with yukata, reversible hanhaba obis are popular: they can be folded and twisted in several ways to create colour effects. A hanhaba obi is 15 centimetres (5.9 in) wide and 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long. Tying it is relatively easy, and its use does not require pads or strings. The knots used for hanhaba obi are often simplified versions of bunko-musubi. As it is more “acceptable” to play with an informal obi, hanhaba obi is sometimes worn in self-invented styles, often with decorative ribbons and such.

-

- Kobukuro obi (小袋) is an unlined hoso obi whose width is 15 centimetres (5.9 in) or 20 centimetres (7.9 in) and length 300 centimetres (9.8 ft).

- Hara-awase obi (典雅帯) or chūya obi is an informal obi that has sides of different colours. It is fequently seen in pictures from the Edo and Meiji periods, but today it is hardly used. A chūya obi (“day and night”) has a dark, sparingly decorated side and another, more colourful and festive side. This way the obi can be worn both in everyday life and for celebration. The obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.

- Heko obi (兵児帯, , ”soft obi”) is a very informal obi made of soft, thin cloth, often dyed with shibori. Its traditional use is as an informal obi for children and men and there were times when it was considered totally inappropriate for women. Nowadays young girls and women can wear a heko obi with modern, informal kimonos and yukatas. An adult’s heko obi is the common size of an obi, about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) to 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and about 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) long.

- Hitoe obi (単帯) means “one-layer obi”. It is made from silk cloth so stiff that the obi does not need lining or in-sewn stiffeners. One of these cloth types is called Hakata ori. A hitoe obi can be worn with everyday kimono or yukata. A hitoe obi is 15 centimetres (5.9 in) to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide (the so-called hanhaba obi) or 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and about 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.

- Kyōbukuro obi (京袋帯, , “capital fukuro obi”) was invented in the 1970s in Nishijin, Kyoto. It lies among the usage scale right between nagoya obi and fukuro obi, and can be used to smarten up an everyfay outfit. A kyōbukuro obi is structured like a fukuro obi but is as short as a nagoya obi. It thus can also be turned inside out for wear like reversible obis. A kyōbukuro obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) long.

- Maru obi (丸帯, , “one-piece obi”) is the most formal obi. It is made from cloth about 68 cm wide and is folded around a double lining and sewn together. Maru obis were at their most popular during the Taishō- and Meiji-periods. Their bulk and weight makes maru obis difficult to handle and nowadays they are worn mostly by geishas, maikos and others such. Another use for maru obi is as a part of a bride’s outfit. A maru obi is about 30 centimetres (12 in) to 35 centimetres (14 in) wide and 360 centimetres (11.8 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long, fully patterned and often embroidered with metal-coated yarn and foilwork.

- Nagoya obi (名古屋帯), or when differentiating from the fukuro Nagoya obi also called kyūsun Nagoya obi (九寸名古屋帯, , “nine inch nagoya obi”) is the most used obi type today. A Nagoya obi can be told apart by its distinguishable structure: one end is folded and sewn in half, the other end is of full width. This is to make putting the obi on easier. A Nagoya obi can be partly or fully patterned. It is normally worn only in the taiko musubi style, and many Nagoya obis are designed so that they have patterns only in the part that will be most prominent in the knot. A Nagoya obi is shorter than other obi types, about 315 centimetres (10.33 ft) to 345 centimetres (11.32 ft) long, but of the same width, about 30 centimetres (12 in).

Nagoya obi is relatively new. It was developed by a seamstress living in Nagoya at the end of the 1920s. The new easy-to-use obi gained popularity among Tokyo’s geishas, from whom it then was adopted by fashionable city women for their everyday wear. - The formality and fanciness of a Nagoya obi depends on its material just like is with other obi types. Since the Nagoya obi was originally used as everyday wear it can never be part of a truly ceremonial outfit, but a Nagoya obi made from exquisite brocade can be accepted as semi-ceremonial wear.

- The term Nagoya obi can also refer to another obi with the same name, used centuries ago. This Nagoya obi was cord-like.

- Odori obi (盆踊帯, , “dance obi”) is a name for obis used in dance acts. An odori obi is often big, simple-patterned and has patterns done in metallic colours so that it can be seen easily from the audience. An odori obi can be 10 centimetres (3.9 in) to 30 centimetres (12 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 450 centimetres (14.8 ft) long. As the term “odori obi” is not established, it can refer to any obi meant for dance acts.

- Sakiori obi is a woven obi made by using yard or narrow strips from old clothes as weave. Sakiori obis are used with kimono worn at home. A sakiori obi is similar to a hanhaba obi in size and extremely informal.

- Tenga obi (典雅帯, , “fancy obi”) resembles a hanhaba obi but is more formal. It is usually wider and made from fancier cloth more suitable for celebration. The patterns usually include auspicious, celebratory motifs. A tenga obi is about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) wide and 350 centimetres (11.5 ft) to 400 centimetres (13 ft) long.

- Tsuke obi (付け帯) or tsukuri obi (作り帯) or kantan obi is any ready-tied obi. It often has a separate, cardboard-supported knot piece and a piece that is wrapped around the waist. The tsuke obi is fastened in place by ribbons. Tsuke obis are normally very informal and they are mostly used with yukatas.

Accessories for women’s obi

The structure of the common drum bow (taiko musubi). Obijime is shown in mid-shade grey, obiage in dark grey. Obimakura is hidden by the obiage.

- Obiage is a scarf-like piece of cloth that covers up the obimakura and keeps the upper part of the obi knot in place. These days it is customary for an unmarried, young woman to let her obiage show from underneath the obi in the front. A married woman will tuck it deeper in and only allow it to peek. Obiage can be thought of as an undergarment for kimono, so letting it show is a little provocative.

- Obidome is a small decorative accessory that is fastened onto obi jime. It is not used very often.

- Obi-ita is a separate stiffener that keeps the obi flat. It is a thin piece of cardboard covered with cloth and placed between the layers of obi when putting the obi on. Some types of obi-ita are attached around the waist with cords before the obi is put on.

- Obijime is a string about 150 centimetres (4.9 ft) long that is tied around the obi and through the knot, and which doubles as decoration. It can be a woven string, or be constructed as a narrow sewn tube of fabric. There are both flat and round obijimes. They often have tassels at both ends and they are made from silk, satin, brocade or viscose. A cord-like or a padded tube obijime is considered more festive and ceremonial than a flat one.

- Obimakura is a small pillow that supports and shapes the obi knot. The most common knot these days, taiko musubi, is made using an elongated round obimakura.

History of the Obi

In its early days, an obi was a cord or a ribbon-like sash, approximately 8 centimetres (3.1 in) in width. Men’s and women’s obis were similar. In the beginning of the 17th century both women and men wore a ribbon obi. By the 1680s the width of women’s obi had already doubled. In the 1730s women’s obis were about 25 centimetres (9.8 in) wide and at the turn of the 19th century even as wide as 30 centimetres (12 in). At that time separate ribbons and cords were already necessary to hold the obi in place. Men’s obi was at its widest in the 1730s, being about 16 centimetres (6.3 in) wide.

Before the Edo period which began in 1600, women’s kosodes were fastened with a narrow sash at the hips. The mode of attaching the sleeve widely to the torso part of the garment would have prevented the use of wider obis. When the sleeves of kosode at the beginning of Edo period began to grow in width (i.e. in length), the obi widened as well. There were two reasons for this: firstly, to maintain the aesthetic balance of the outfit, the longer sleeves needed a wider sash to accompany them — and secondly, unlike today, married women also wore long-sleeved kimono in the 1770s. The use of long sleeves without leaving the underarm open would have hindered movements greatly. The underarm openings in turn gave room for even wider obis.

Originally all obis were tied in the front. Later on fashion began to affect the position of the knot and obis could be tied to the side or to the back. As obis grew wider the knots grew bigger, and it was becoming cumbersome to tie the obi in the front. In the end of the 17th century obis were mostly tied in the back. However, the custom did not become established before the beginning of the 20th century.

At the end of the 18th century it was fashionable for a woman’s kosode to have overly long hems that were allowed to trail behind when in house. For moving outside, the excess cloth was tied up beneath the obi with a wide cloth ribbon called shigoki obi. Contemporary kimonos are made similarly over-long, but the hems are not allowed to trail; the excess cloth is tied up to hips, forming a fold called ohashori. Shigoki obis are still used, but only in decorative purposes.

The most formal of obis are about to become obsolete. The heavy and long maru obi is nowadays used only by maikos and brides as a part of their wedding outfit. The lighter fukuro obi has taken the place of maru obi. The originally everyday nagoya obi is the most common obi used today, and the fancier ones may even be accepted as a part of a semi-ceremonial outfit. The use of musubi, or decorative knots, has also narrowed so that women tie their obi almost solely in the simple taiko musubi, “drum knot”. Tsuke obis with ready-made knots are also gaining in popularity.

Photos: http://satokhi.exblog.jp/

A Celebration of Women

sends our blessings to all the children of JAPAN.

Celebrate Your Right of Passage!